Jorhat (Assam) – When Indranil Sharma took over the management of Sotai Tea Estate from his ailing father about 15 years ago, he was staring at a liability of more than a million U.S. dollars.

With banks refusing financial assistance and authorities threatening to sue him for defaulting on workers' dues for several years, Sotai’s story under the Sharma family appeared like it was in its last chapter.

Hitherto Sotai was just an average garden located on the outskirts of Jorhat district in eastern Assam, making black tea for which Assam is famous for.

However, a never-give-up attitude of Sharma and a long struggle earned him what any tea planter would dream for. Sotai today is one of the few gardens which have been continuously in the list of top 10 tea estates in India, as far as prices are concerned for black tea. Sotai’s success story was recognized by none other than the Federation of All India Tea Traders’ Association (FAITTA) recently, at a function held at Kolkata in West Bengal. Sharma was felicitated in presence of the who’s who in the Indian tea industry.

“My only mantra for success is I focused on providing the best cup of tea to the consumer,” Sharma told the World Tea News.

The History of Sotai Tea Estate

The 163-hectare Sotai Tea Estate was an average garden among many that dot Assam’s landscape when the Sharma family took over possession of the estate in 1974 from a company called Kothari planters. Things were going smooth at Sotai with the Sharmas moving to the garden lock, stock and barrel to concentrate totally on the tea business.

Tea was a lucrative business in those days, and tea estate owners were considered the high and mighty in the society, who followed the legacy left behind by their British predecessors. Soon after the British – who started tea cultivation commercially in Assam in the 1830s after the East India Company lost its hold over the Chinese tea trade – left India, many local planters took to tea business. While a few took possession of the plantations – which were established by the Englishmen – many started planting tea bushes by clearing forest land in remote areas.

Plantation of Camellia Sinensis at Sotai was started by a British company – Kingsley, Golaghat.

Though Indranil grew up in the tea estate, he never took interest in the tea making process and was shifted to the capital city of Assam, Guwahati, about 300 Km from Jorhat, to literally enjoy his life with a house and a fleet of cars in his possession in the early 1990s. Clubs, parties became his way of life.

Things started getting bad at Sotai when the tea industry in India plunged into a severe crisis – mainly due to rise in cost of production and no significant increase in prices and export since 1998. During that period, auction prices hovered between Rs 70 per kg to Rs 100 per kg, whereas cost of production had touched almost Rs 150 per kg. Many small gardens had closed shop during that period, and big companies also sold off many tea gardens. Incidents of attacks on tea garden executives by irate laborers became a common feature in the Assam tea industry in those days.

Experts in the industry, though, blamed the ever increasing number of small tea growers and numerous bought leaf factories which came up in Assam during the early 1990s for production of poor quality tea. In fact, the Tea Board of India had warned that if the producers did not concentrate on quality, the tea industry in Assam would no longer be sustainable.

“I had got a warning from my father that things were not good at Sotai, and I had to return home as it was becoming difficult to meet my expenses at Guwahati,” Sharma said.

Those were bad days at Sotai with threats from workers for not getting their weekly wages becoming a regular affair. Forget about other facilities like rations, medicines, et al. Electricity was discontinued due to accumulation of huge dues.

‘I Had No Idea About Tea Making and There Was No Help from Anyone’

Sharma landed up at Jorhat in the wee hours of a July morning – peak production season in Assam tea – travelling on a night service public transport bus from Guwahati back home. He was picked up at the bus station by a rickety Fiat car, the only mode of transportation of Sotai Tea Company then, to reach home 14 km away. “I reached home at around 6 a.m. and was having a cup of tea when I saw workers gathering outside my house,” he recalls. The news of Sharma reaching home had already spread in Sotai and the disgruntled workers, a few armed with sharp weapons, were after his blood.

"I went out to face them, almost sure that my life is at their mercy,” Sharma recalls. Only a few months back, an owner of a tea estate in neighboring Golaghat district was lynched by the laborers under similar circumstances.

Be it the grace of God or the convincing power of Indranil, the workers of Sotai agreed to cooperate with the management. “I pleaded with them to give me some more time and begged for their cooperation…I don't know how but they believed me,” Sharma said.

That was the beginning of a new chapter at Sotai.

“I felt like I was in the middle of the sea on a rudderless boat. I had no idea about tea making and there was no help from anyone,” Sharma explained.

Sharma said that he and his wife Babi, a strong lady, decided to go to Kolkata to the bank headquarters, seeking help leaving his two kid daughters at the garden with his old parents and without electricity connection. “We spent more than a month at Kolkata, staying at a relative’s place going to the bank daily in the morning, almost begging them for help,” he said. The bank first refused to finance outright, but with much cajoling, it agreed but on a condition that it would take over Sotai if the loans were not cleared within the stipulated time frame.

“I had no option left but to sign on the dotted line,” Indranil said.

Indranil returned to Sotai and it was a do or die situation at hand.

“First I removed the executives to cut costs. Then I approached an experienced labor leader and asked him to teach me the process of making tea,” he said.

The Success of a Tea Estate

It took Sharma two years to learn the trick of making tea – good tea that is.

From plucking tea leaves, pruning, adding fertilizers to tea bushes, the factory activities all took place under the watchful eyes of Sharma, whereas his wife concentrated on the paper works.

By then, Sotai had become a one-man show.

Indranil has given up on all social activities and concentrated on tea making.

“I remember not going out of the garden for months together. It has become my routine to spend at least six hours in the garden working with the laborers. I do my accounts in the evenings,” said Sharma.

Sotai – in the last five years – has not only managed to clear its bank liabilities but has also paid all the pending dues of the labor force – who, according to Sharma, is his family. “Without the support of the workforce one cannot simply sustain. I make it a point to interact with the laborers almost daily like a family member,” he said.

At Sotai, the workforce today considers Sharma not as the owner of the garden but as the head of the family.

“He [Sharma] is our mai baap [father/mother] …he takes good care of us,” Naga Karmakar, a worker at Sotai, said.

Like the labor force, Sharma also pays the same attention to the tea bushes of his estate. “There are nearly two million tea bushes in my garden…” he said.

80 / 20 to Make Good Tea

According to Sharma, to make good tea it is 80 percent of field work and only 20 percent happens in the factory. “Unless good leaves are plucked from the bush it would be impossible to make quality tea,” he said.

Sotai today produces 2.20 lakh kgs of top-quality CTC tea annually. The last sale at the Guwahati Tea Auction Centre, one of busiest tea trading facilities in the world, Sotai managed to fetch Rs 500 for a kg of tea, the best-ever price for Sotai tea. Only a handful of gardens in India managed to achieve such heights. “This is the beginning and I have miles to go,” Sharma said.

Ajit Sharma, a retired tea scientist of the Tocklai Tea Research Institute, said the best thing about Sharma was that he believes in the scientific approach in making tea. “We have interacted many times and he always follows the advice we provide. That is one of the reasons for Sotai’s success,” he said.

A Positive Outlook Equals a Bright Future

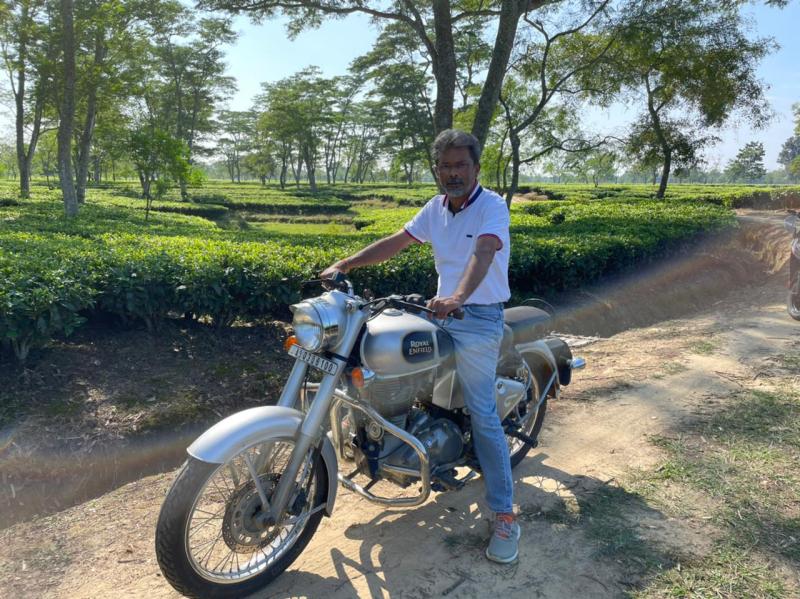

It was 2.30 p.m. at Sotai and the September sun was in full blaze with humidity at its peak unlike earlier times. Sharma suddenly stops his Royal Enfield motorcycle as he rides through a narrow road between the tea bushes. He alights from his two-wheeler and approaches a particular patch of tea bush. “Hell with these tea bugs…” he says in exasperation.

But he had overcome many before.

Pullock Dutta – based in Assam, near the Tocklai Tea Research Institute – is a freelance journalist, contributor to World Tea News, and a previous special correspondent of the Telegraph in India for more than two decades.

Plan to Attend or Participate in the

World Tea Conference + Expo, March 21-23, 2022

To learn about other issues, trends and hot topics within the global tea community, plan to attend the World Tea Conference + Expo, March 21-23, 2022, celebrating its 20th anniversary. World Tea Conference + Expo will be co-located with Bar & Restaurant Expo, creating unique opportunities and synergy. Visit WorldTeaExpo.com.

To book your sponsorship or exhibit space at the World Tea Conference + Expo, co-located with Bar & Restaurant Expo, contact:

Veronica Gonnello

Companies A-L

e: [email protected]

p: 1 (212) 895-8244

Fadi Alsayegh

Companies M-Z

e: [email protected]

p: 1 (917) 258-5174

Also, be sure to stay connected with the World Tea Conference + Expo on social media, for details and insights about the event. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.